FOR PARENTS/WHĀNAU

There is plenty that parents/whānau can do with their children from birth onwards to help them get off to a great start in literacy.

Under 5's

It matters what children do before they start school.

Giving your child a head start in literacy can be easy, fun and at little to no cost. It can also begin at any age.

Young children are like sponges in the first few years of their life. They take in everything they see and hear, even if it doesn’t always seem like they are paying attention. They learn from experience, and simple daily activities can help them develop phonological awareness from an early age.

As a parent and teacher with a passion for literacy, Yolanda has seen firsthand the difference the following strategies can make in a child’s development.

Yolanda’s key strategies for setting up the Under 5’s for later success in literacy.

Develop phonological awareness

It has been shown repeatedly that children who start school with good phonological awareness have better literacy outcomes.

Some easy and fun ways to help develop your under 5’s phonological awareness include:

Listen to music, nursery rhymes, and songs for children (Yolanda recommends Tessarose and Love to Sing).

When reading, talk about the stories, point to the pictures, make the noises of the animal characters (Yolanda recommends Eardrops).

Use sound lotto games such as Listening Lotto and Sound Tracks to develop a wide repertoire of known sounds.

Top tip: Yolanda’s book Developing Phonological Awareness is packed with quick practical activities you can do with your child from birth. Parents are also welcome to take part in a Developing Phonological Awareness training webinars with Yolanda to learn how to effectively develop phonological awareness with their child.

Top tip: Yolanda’s book Developing Phonological Awareness is packed with quick practical activities you can do with your child from birth. Parents are also welcome to take part in a Developing Phonological Awareness training webinars with Yolanda to learn how to effectively develop phonological awareness with their child.

Develop graphic knowledge

The skills required to be able to visually discriminate between words are laid down well before children read their first book. Games and activities where children must use visual information to match or separate one item from another visually will hone this skill.

Teach your child the principle of ‘same same’:

Smart Tray with the Early Accelerator card system.

Did you know that children can learn to read their name from the age of two years, if not earlier?

Develop oral language.

Talking to and with your child from birth is vitally important. Many studies have shown that the quantity of language spoken to the child predicts their later vocabulary and progress in literacy.

Have conversations. Talk about stories, people, places. Talk talk talk and read, read, read.

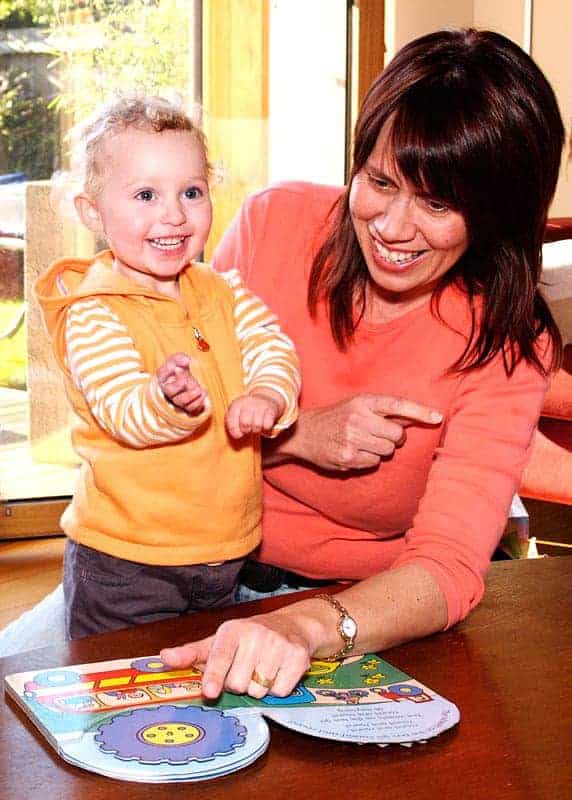

Read to children

Start at birth and continue until they leave home. There is no reason to stop reading to your child. Did you know that children’s picture books have three times more interesting words in them than the conversation of university graduates? Building vocabulary early has long-term positive benefits for young readers.

Reading to children extends vocabulary, oral language, phonological awareness and opens the world for children. Read at least five stories over the day with your child. Also include rhymes and poems.

THE CHECKLIST:

Yolanda’s favourite books for babies and toddlers

Hairy Maclary, Lynley Dodd

We’re going on a bear hunt, Michael Rosen & Helen Oxenbury

My cat likes to hide in boxes, Eve Sutton

Brown bear, brown bear, what do you see?, Bill Martin Jnr

Each peach, pear, plum, Janet & Allan Ahlberg

An anthology of nursery rhymes such as This Little Puffin

Yolanda’s favourite books for pre-schoolers

Farmer Duck, Martin Waddell

The Gruffalo, Julia Donaldson

Animalia, Graeme Base

The Story of Ferdinand, Munro Leaf

Dr. Seuss books

plus classic traditional tale books

Children aged 5-7 years

Parents know that for children to be successful in literacy, they need to be able to work out new words, sounding them out for reading and spelling.

Yolanda has trained over 20,000 teachers in New Zealand and overseas on how to help children do this. Her ideas can also be used by parents who want to actively support and help their children read and write.

School ready literacy check

Being school-ready for literacy means starting school with the skills in place to optimise your child’s first formal literacy learning experiences.

THE CHECKLIST:

Understanding phonics

Phonics is not just knowing how to hear, read and write sounds/letters. It is also knowing how to use these sounds (phonemes) for blending and segmenting for use in reading and writing.

The starting place, once phonological awareness is developed, is the alphabet. Children need to know all the letter sounds, names, and word associations. As the brain is wired for story, it is helpful to tell children little stories (mnemonics) about each letter to teach the sound, word association, and letter name.

Yolanda has created an alphabet mnemonic scheme with short letter stories and word associations that is free and fun for for parents and whānau to use.

Yolanda has created an alphabet mnemonic scheme with short letter stories and word associations that is free and fun for for parents and whānau to use.

The mnemonic is also available to purchase in a handy pocket-sized card pack.

We also have letter flashcards and an alphabet wall frieze that could be used in their bedroom for a fun and educational wall decor. The playdough letter mats are also a fun way to learn letters whilst developing motor skills and the muscles in the hands required for writing.

A smart tray with the Phonemic Awareness card set offers a hands on way for children to practise their phonic skills.

Yolanda’s Alphabet Sounds (NZ) App allows children to hear, read and write the letters for the alphabet sounds. it is available in both the Google Play and Apple stores for a $3.49 annual subscription.

Yolanda’s Alphabet Sounds (NZ) App allows children to hear, read and write the letters for the alphabet sounds. it is available in both the Google Play and Apple stores for a $3.49 annual subscription.

What are high-frequency words?

High-frequency words (also known as sight or heart words) appear most frequently in a text, e.g., the, is, my, go, come. Did you know that only 100 words make up half of all text? When children learn these common words, it allows their brain to figure out the other words they don’t know yet. Over time, children develop an ever-increasing memory bank of words until eventually every word is known and they have extensive graphic knowledge. Reading is much easier when you can recognise all the words and do not have to stop to figure them out.

It takes time to develop graphic knowledge. The teaching of phonics gives children a way to get to a word they haven’t seen before. Some words, however, are not easily figured out (decodable), e.g., was, saw, my, I. For these words, it is usually quicker to teach the child to recognise them by sight.

Yolanda developed the Early Words programme for teachers, parents and whānau to help their children learn the basic sight words. She used her programme to teach her four children before they started school and has taught many other students and teachers since. Early Words has been used in schools in the UK and New Zealand with much success.

The Early Words book contains instructions on how to teach the programme. But parents and whānau are welcome to do the online Early Words course for practical experience in teaching the programme.

The Early Words book contains instructions on how to teach the programme. But parents and whānau are welcome to do the online Early Words course for practical experience in teaching the programme.

-

Early Words 2

$67.00In stock

-

Early Words

$75.00In stock

Learn to Read

Learning to read doesn’t happen overnight; it takes time, but there are several things you can do to help your child when they stumble or get stuck on a word. You can:

Note

If the child is challenged by more than one word in every ten, the book is too hard. Either you read the story to them or take turns reading each page or unknown word so reading does not feel like a struggle. Struggling does not help children learn to read. When it is too difficult, it is harder to learn, and there is little enjoyment and motivation to read.

Tip

Encourage your child to read using their finger to follow the words at this early stage. They can stop using their finger once they understand the one-to-one matching of words. It is okay to read the same book again and again as it helps develop fluency in reading, expression and confidence.

The video is of Yolanda teaching her nephew to read a guided reading book.

Yolanda has written 50 Early Words guided reading books to help children first experience reading themselves. These books are used in many schools, but they are also available for purchase. The first book in set one is called Mum, as this is one of the first words a child learns to read. Each book expands a little on the previous one in the set, introducing a new word and repeating others already used. For example, Mum is followed by Mum is Exercising, where the next word ‘is’ is taught. The stories are character driven and have some decodable words. We recommend using the books in sequence, working your way one book at a time through the different reading levels.

Children love the Early Words Readers characters and stories. And they feel confident and successful being able to read their own little book.

Yolanda was interviewed in 2021 by Jesse Mulligan on RNZ about how she developed and wrote the Early Words Readers.

Learning to write

Learning to write is a complex process. Many children find it particularly challenging to spell words. Here are some useful suggestions to help your child correctly spell a word.

Note

Check that the word your child wants to spell is easily sounded out. For example, words such as ‘saw’ and ‘here’ are hard to sound out for beginning writers who don’t yet have advanced phonics knowledge. For these words, let your child hear and record the first sound and then you can complete the word for them.

Specific Learning Difficulties (SLDs) can include dyslexia, dysgraphia, difficulties with memory, organisation, auditory and visual processing, time management skills, and more. These difficulties can have a big impact on literacy learning

Yolanda is a mother of children with severe Specific Learning Difficulties. Knowing that the education system is not resourced to properly help children with these difficulties, she taught her own children plus used a wide variety of learning and support programmes throughout their education.

Yolanda’s advice to parents of children with SLDs

Read How My Brain Learns to Read by Duncan Milne to your child.

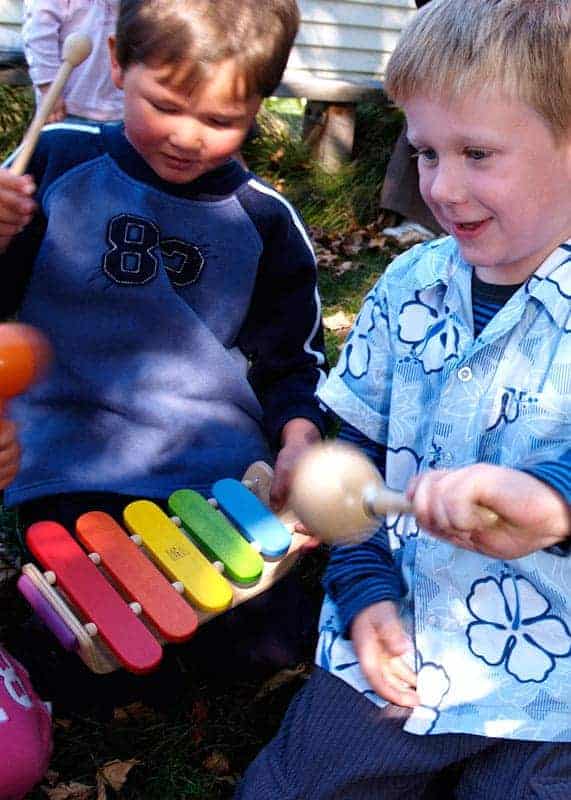

In this Ted talk, educator Anita Collins makes a passionate case for music education as an indispensable part of school curricula, describing how learning to play music is the neurological equivalent of a full-body workout.

-

DIY Playdough Letter Mats

$15.00In stock

-

Early Words

$75.00In stock

-

Phonics/Word (PW) card

$2.50 – $20.00In stock

-

Letter and Mnemonic Cards sets

$15.00 – $25.00In stock

-

Alphabet Wall Frieze

$15.00 – $35.00In stock